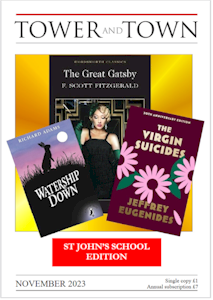

Tower and Town, November 2023 (view the full edition) (view the full edition)Thoughts Invoked By LiteratureYear 13 student, Emma Wing employs the perspective of one of the novel’s characters when conveying her experience of reading the same novel: The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides. When Cecilia kills herself, I am observing the boys’ mother invited to the party. An odd collection of faces: some rough, others round, spotted with snub noses and pixie ears, but all with the same protruding pupils, boring into the abyss between us in desperation to draw us near. Mother has dug a chasm in the centre of the room: to protect us from their careless values and soft jaws, aching to turn into stubble and sinew, mocking mother’s efforts to stagnate the surging flow of adolescence. But I think it is more for their sake the room remains ruptured. If spotted, the shy threads of hair on Mary’s upper lip could unravel whatever story the boys have spun of us. Might the boys understand my sisters and me? After all, they have come to a party in the Lisbon house – a strange, wounded animal, lying bloody on the street like roadkill. But when we see them through the twitch of their curtains, those same buggish eyes pulsing with reckless excitement at our catching them, or we pass them gathering gossip from their mothers in the street, we know we’ll always be unknown to them. We may be wallpaper to our parents, but we are hanging artwork to those boys- pretty pictures that plump the egos of those who think they can infer our meanings, but ultimately walk away when they’ve looked at our colours a little too long. I wonder if the world forgets that my sisters and I are real, with our feet planted on the soil and not floating somewhere above. Ghostly to many and cruelly angelic to those boys, I know that my sisters and I are anything but: reality has bound us, our only escape to burrow further into the earth. I am thinking about this when Cecilia asks to go upstairs; she keeps tugging at the bracelets on her wrists with eyelids downturned like wilting petals dropping closer to the floor. She was happy this morning when we were all in our room, singing to the record Lux had snuck from under her bed and comparing the feeble muscles in our arms. Is the boys’ presence ageing her, trussing her up into a womanly figure instead of the mess of a girl she is? So, in the seconds later, when Cecilia flings herself to her death, part of me knows that she did not jump from that ledge but was pushed by the hands of Time and the restless boys who willed its minutes to tick faster in their greed to turn a young girl into an object of shared fantasies. Bloody and broken, like an effigy of a biblical sacrifice, our eyes meet the mass of white and red that is now my sister: how can she look so perfectly pure - frozen in a state of girlhood- when God was clearly never on her side? How can our own thirst for violence burn in our throats when we spy her punctured chest? In books, it is always women who suffer the impalement of fence spikes and the sting of society’s cold shoulder, yet my sister was more than a battleground but a real, beating heart of frustration and longing, the same as any boy. Yet when herded into a corner, by futile parents and an all-knowing town, the wounded animal has no-one left to bite but itself. Lux jokes that whilst the boys over the road may feature briefly in our lives as passing thoughts of puzzlement and possibility, they’ll likely write novels about us. I wonder whether through their words we will become as hazy and hollow as the women on our shelves- as purely physical as the literature our mother plans to burn- or if something more could be spooned from us: if a girl like myself could pick up the pages and see the honest truth that all had failed to recognise- that no amount of clinical love or prying obsession can ease, or comprehend, the horror of being a teenage girl in a world that does not care. Maybe she could read our story and understand that being a young girl is scary and unrelenting, like a raging fire, yet simultaneously thrumming with sparkling, unadulterated hope. None of us Lisbon girls were understood as beautiful in the ways that mattered. Yet perhaps the girl who reads our story won’t only see us for more than our suffering, but grow to see herself and others through unclouded eyes too. Emma Wing (y13) |