Tower and Town, May 2020 (view the full edition) (view the full edition)A New Museum In Iraq

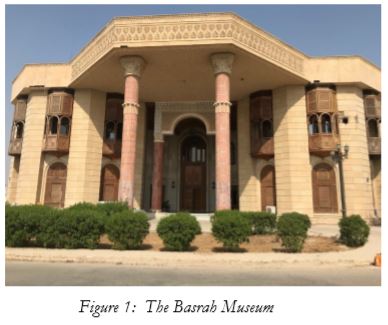

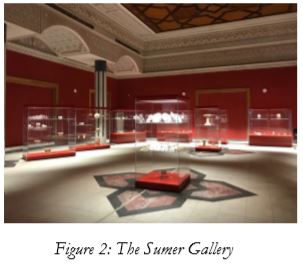

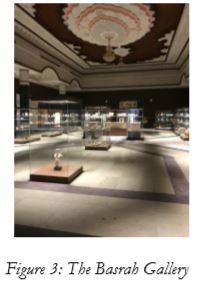

Oxford University’s Ashmolean Museum is the oldest public museum in the UK (established in 1683) but its collections from the ancient Middle East were largely formed in the first half of the twentieth century, a direct result of British occupation and administration of large parts of Palestine (modern Israel, Jordan and Palestinian Authority) and Mesopotamia (modern Syria and Iraq) following the end of the First World War. Such a legacy can be viewed as problematic and, as the current curator for the Ashmolean’s Ancient Middle East collections, I am working with colleagues to create new displays and a temporary exhibition which will not only reveal the region’s ancient stories but tell something of this recent history and the importance of heritage for the region’s modern inhabitants. One of the most exciting projects that I have had the privilege of supporting is the development of an archaeology museum for Basrah, Iraq’s second city. To understand the Basrah Museum project it is necessary to understand the longer history of museums in Iraq. This story starts in the aftermath of the First World War with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire by allied forces. Britain, who had occupied Ottoman Mesopotamia (the land ‘between the rivers’ Tigris and Euphrates) during the war, was granted mandate control over the region. After a major rebellion against the occupation in 1920, a Kingdom of Iraq was established the following year under British administration. European and North American Universities and museums were already applying pressure in these years to undertake archaeological excavations and shortly after the signing of the Anglo-Iraq treaty of 1922, a Department of Antiquities was created with Gertrude Bell - traveller, writer, archaeologist and civil servant (the British administration’s Oriental Secretary in Baghdad) – as its Honorary Director.  After Britain formally withdrew from Iraq in 1932 the former Education Minister Sati al-Husri became the first Iraqi Director General of Antiquities. He revised Bell’s antiquities laws in Iraq’s favour, and the first Iraqi-led excavations were carried out. Planning began for a much larger and more accessible museum but it was not until after the Second World War that it became a reality; the Iraq Museum was opened in 1966. With the oil boom of the 1970s and 1980s regional museums were established across the country. The Iraq Museum delivered to them highly uniform mini-collections of artefacts to display so that the single, unifying story could be told from Dohuk in the north to Basrah in the south (where the museum was housed in a fine Ottoman building of the early 20th century). Then came the disasters of First Gulf War of 1990-91. Many provincial museums, including that in Basrah were looted in the post– war Shia uprisings of spring 1991 and then stayed permanently shut. The Second Gulf war and invasion of 2003 (the third time in a century that British forces had occupied Iraq) brought more misery with the looting of the Iraq Museum and Mosul Museum. In 2007 a project to develop a new museum for Basrah was initiated by Lieutenant General Barney White-Spunner who had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of British troops in Iraq and General Officer Commanding the Multi-National Division South-East. He was due to be deployed to Iraq in February 2008, and wanted to know what he might do to help protect Iraqi cultural heritage. Following a meeting at the British Museum with its director Neil MacGregor and Dr John Curtis, head of the museum’s Middle East Department, White-Spunner assigned Major Hugo Clarke as project manager. The State Board had appointed Qahtan Al Abeed as the director of any future Basrah Museum and he began to work closely with Clarke. A former palace of Saddam Hussein known as “the Lakeside Palace”- which I first visited with John Curtis in 2008 - was adopted as a possible candidate for the museum. However, with no prospect of any British government funding, and the withdrawal of the British army in 2009, a UK charity Friends of Basrah Museum was established to help raise funds. Years passed waiting or money promised by Basrah Provincial Council but, as Iraq continued to be plagued by conflict and corruption, this was never forthcoming. Therefore, with the agreement of Qahtan and the Iraqi authorities, the Friends of Basrah decided to use their funds to refurbish one gallery devoted to the history of Basrah; it was opened to the public in September 2016 and was celebrated with an international conference that I attended. An application was then made to the British government’s newly formed Cultural Protection Fund for a grant to complete the museum. This was successful and in 2018 I led a training course for the museum staff and, by March 2019, three more galleries, devoted to ancient Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria had been opened; objects for the museum had been selected by Qahtan from the stored collections in the Iraq Museum. I was back at the Museum in October 2019 and discovered that great strides have been made in creating a building that is now welcoming increasing numbers of visitors. Qahtan had already produced object labels in Arabic and we focused on translations into English. Future work will be the establishment of a modern library on the upper floor of the museum. The aim is to make the museum a cultural resource for academic research as well as popular enjoyment. This is part of a wider initiative now fully supported by the Basrah Provincial Council to refurbish neighbouring buildings and lay out surrounding parks, all adjacent to the waters of the Shat al-Arab, in order to make this part of the city a focus for families and cultural events into the future.   Paul Collins is Jaleh Hearn Curator of Ancient Near East in the Department of Antiquities at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University, and is currently a Hugh Price Fellow at Jesus College and holds a supernumerary Fellowship at Wolfson College. He has worked previously as a curator in the Middle East Department of the British Museum and the Ancient Near Eastern Art Department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. He is currently Chair of the British Institute for the Study of Iraq. Paul Collins |