Tower and Town, May 2020 (view the full edition) (view the full edition)

Zaha, A Planet In Her Own Orbit

When I was growing up in Iraq, mathematics was an everyday part of life. My parents instilled in me a passion for discovery, and they never made a distinction between science and creativity. We would play with math problems just as we would play with pens and paper to draw -- math was like sketching. In my teens, my family would go to London each summer, visiting the many art galleries and museums, including the Science Museum. I am forever grateful to my parents for introducing me to art and science in a way that drew no boundaries between them. I believe education at all levels is critical. As a woman, education gives you the confidence to conquer the next step and make exciting new discoveries. (Zaha Hadid, 2015)

A Flame Burned Brightly

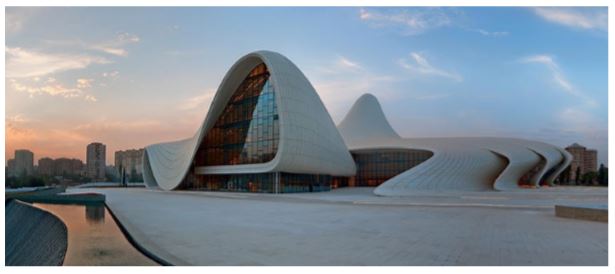

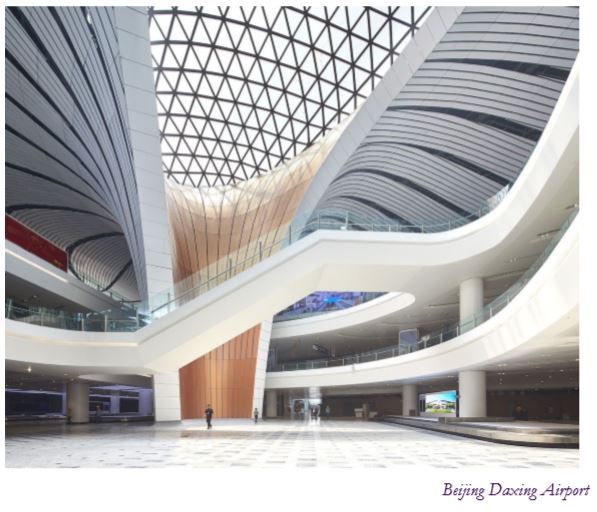

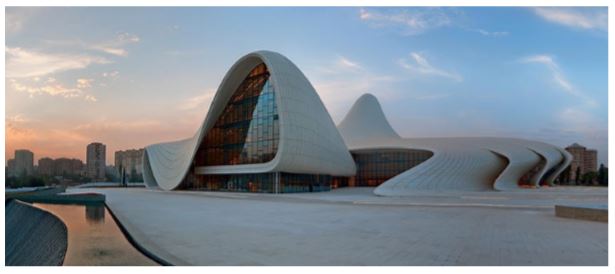

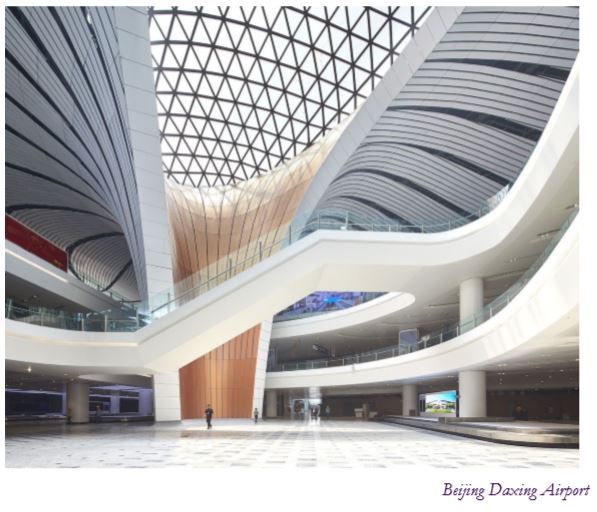

Accredited by the Guardian Newspaper for liberating architectural geometry, giving it a whole new expressive identity, Dame Zaha Hadid (1950-2016) was the Iraqi-British architect, and the first woman winner of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. She successfully applied advances in design in order to enable re-thinking of space and form for realising wonderful fluid surfaces and structures. Hence she was able to transform cities around the world through structures that most of her contemporaries could never have dared to imagine. Known in the architectural world as the “Queen of Curve,” Zaha loved to eschew linear lines in favour of curvy, futuristic shapes. Her UK legacy includes the London Aquatic centre and the Investcorp Building in Oxford (“At Home with Frodo Baggins”, p11, T&T May 2017). And as a trailblazer Zaha’s flame burned brightly from an early age. She graduated in mathematics from the American University of Beirut and headed to London in 1972 where she met her school friend Zina Kafilmout, (then a UCL postgrad architect). Zaha qualified at the Architectural Association School of Architecture (London), where she was described as “A Planet in Her Own Orbit” and possessor of a kind of mythological aura. She was at that stage inspired by the supermatist work of the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich (the supremacy of pure artistic feeling).

Most importantly, Zaha was a seeker of the un-bounded bigger picture; and it is in this spirit that I endeavour painting a somewhat bigger picture of her by looking east for some of her earlier inspirations.

Imagine

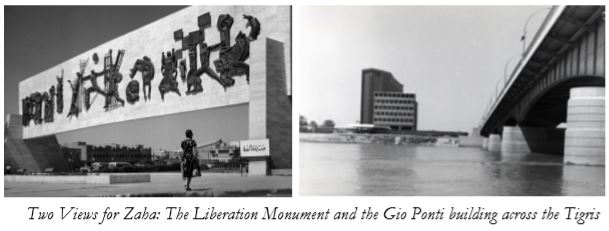

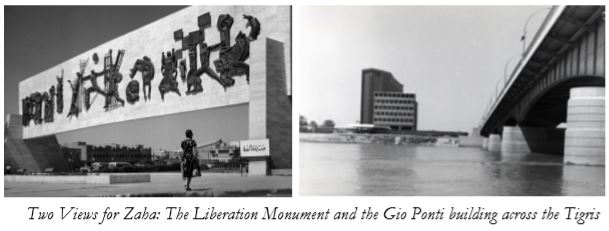

I would like you now to imagine yourself in June 1965 admiring a modern building by the Italian architect Gio Ponti. This building belongs to the Iraqi Ministry of planning situated on the western bank of the river Tigris adjacently to Jisr Al-Jamhuria, (The Republic Bridge).

You would then cross to find your destination immediately on your right, the buildings of Rahibat Al-Taqdama fil Bab Al-Shargi (Secondary/High Convent School at the Eastern Gate). You would also note ahead the striking Nasb Al-Hurriyah, (Freedom Monument), of Tahrir Square.

Now I would like you to imagine being welcomed at the gate of the convent school as a guest for the 5th year leaving ceremony staged by the 4th year students. Founded in 1928 this Catholic school applied high academic rigor and admitted girls from different faiths. On this particular hot June day there would have been an aura of optimism among the pupils. After all, they were a crop of the future makers and heirs of the Abbasid Caliphate flourishing of over millennium earlier. And as six 4th year names were announced for the Hawaii dancing sketch you would have noted those of the two 15 years old girls Zina Kafilmout, (my cousin), and Zaha Hadid (note their 1971 London meeting, previous section). Founded in 1928 this Catholic school applied high academic rigor and admitted girls from different faiths. On this particular hot June day there would have been an aura of optimism among the pupils. After all, they were a crop of the future makers and heirs of the Abbasid Caliphate flourishing of over millennium earlier. And as six 4th year names were announced for the Hawaii dancing sketch you would have noted those of the two 15 years old girls Zina Kafilmout, (my cousin), and Zaha Hadid (note their 1971 London meeting, previous section).

Two Views for Zaha

It was during Zaha’s schooling that Baghdad was central in developing Iraqi/pan-Arab visual language; and that she would have found the modernistic views in the vicinity of her school very stimulating indeed. She would have gazed across the Tigris at the Gio Ponti building, and also at the impressive Freedom Monument, Tahrir Square, with its underlying eastern-western connotations that rendered the product both strikingly modern yet also referenced traditions.

Captured in bronze, the sculpture of this monument symbolises people’s strive against tyranny visualised by the mid-20th century co-founder of the Baghdad Modern Art Group, the late Iraqi painter/sculptor Jawad Saleem, (1919-1961),. Saleem sought celebrating Iraqi art history by incorporating elements of Babylonian wall-reliefs and Abbasid art. The project architect for the monument was the prominent Iraqi architect Rifat Chadirji, who was responsible for pushing architectural boundaries within the context of “International Regionalism” whilst grounded in the discourse of the Baghdad Modern Art Group.

Zaha Hadid: A New Expressive Identity

It is fair to state that cultural/artistic fusions could be liberating for those aspiring to spread their wings; and that Zaha was undoubtedly a true subscriber to this. She grew up in a liberal Baghdadi household with ancestral roots in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul. Her schoolmates were also predominantly from multi-cultural professional families that valued learning and modernity. Moreover, her schooling era was when the capital city was entering its initial phase of ‘metropolization’, in which Baghdad’s courtships of A-list architects, such as Frank Lloyd Wright and le Corbusier, provided means for constructing a progressive identity encompassing elements of spatial modernity. With such rich heritage the outcome was not surprising when the mythical Iraqi bird, Zaha, spread its wings and flew west in order to liberate architectural geometry, giving it a whole new expressive identity.

I am grateful for the invaluable contributions of my cousin Mrs Zina Allos, née Kafilmout. Raik Jarjis |

(view the full edition)

(view the full edition)