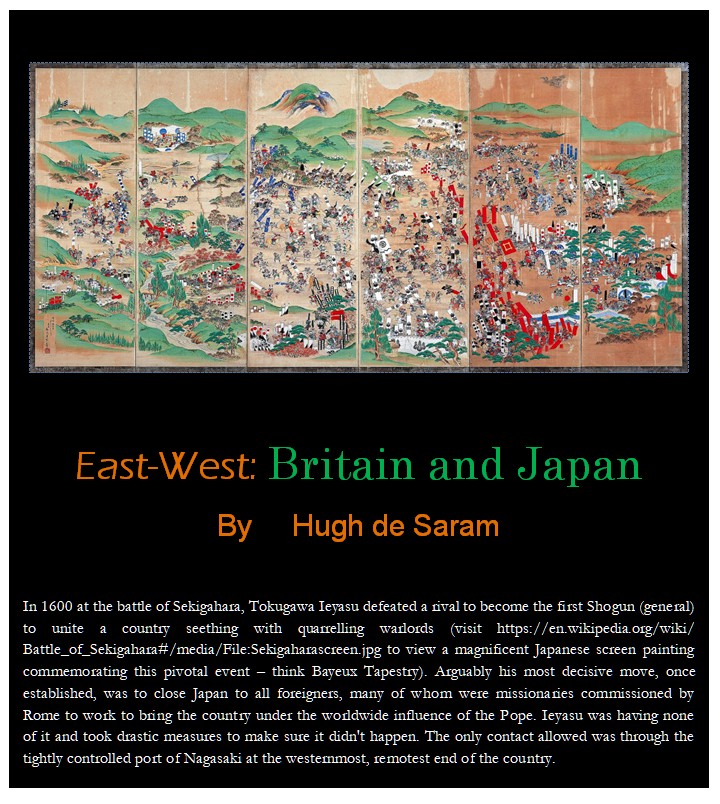

Tower and Town, May 2020 (view the full edition) (view the full edition)Britain and Japan

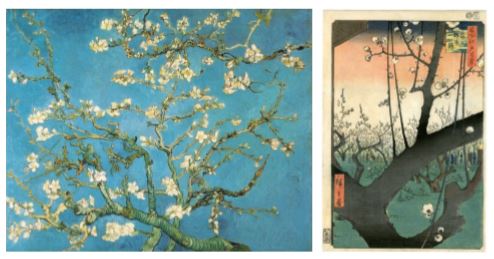

In 1997 I spent a term teaching in a Japanese high school. In one of many eastwest discussions, my Japanese mentor extolled the beneficial effect of Ieyasu's closure of Japan to foreigners on the development of Japan's unique and special culture. I found myself arguing that, from Britain's experience, it was not necessary to close the country to foreigners in order to retain and develop one's unique culture. Indeed, one could argue, Britain's culture had been uniquely enriched by remaining open but fiercely independent; that our continental neighbours regarded us as just as much different in our island fastness as did Japan's continental neighbours in their view of Japan, but that our openness to people, trade and ideas had made us immeasurably the richer whereas Japan, up until the arrival of Commodore Perry 250 years after Sekigahara, was inward-looking and under-developed by comparison. However, in1868 Japan overthrew rule-by-Shogun, re-instated the supremacy of the Emperor (the Meiji Restoration) and reformed itself at breakneck speed to jump from feudalism to western-style democracy. It embarked on a phenomenal catch-up race with the West, leading to its becoming one of the most modern and powerful nations on earth. Japanese culture quickly became the rage in Western Europe. Vincent van Gogh famously acknowledged the influence of Japanese woodblock prints on his own art. He was a particular admirer of Hokusai’s famous Great Wave, and his Blossoming Almond Tree owes an obvious debt to Japan. Hiroshige’s Plum Blossom of 1857 was directly echoed 30 years later in van Gogh’s Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree; after Hiroshige.

The Japanese love Shakespeare. London is regularly visited by Japanese theatre companies playing Shakespeare, in Japanese, to full houses; worth watching, even if you don’t understand Japanese, for their endearingly different stagecraft. Film-maker Akira Kurosawa exemplifies perfectly the interplay between western and eastern culture. On the one hand, Kurosawa took two of Shakespeare’s greatest plays, Macbeth (as Throne of Blood) and King Lear (as Ran), and made them into stunning films. To my mind, his Ran (“Chaos”) is a masterpiece that outdoes its mighty original. On the other hand, western film-makers have equally rendered homage to Kurosawa. Rashomon set a trend illustrating how multiple eyewitnesses of the same event see and remember confusingly contradictory versions; it even gave rise to “the Rashomon effect”. And then of course there is the immortal Seven Samurai, surely one of the best films ever made, most famously copied in The Magnificent Seven. Perhaps most surprisingly, Kurosawa, with other Japanese film-makers, collaborated with American colleagues in the making of the Hollywood blockbuster Tora Tora Tora, portraying the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, that “date which will live in infamy”. My favourite east-west crossover, however, is the shared Anglo-Japanese love of whodunits. Both countries have produced a stream of gripping crime-writers. Two of the best from Japan are Points and Lines, by Seicho Matsumoto – a gift for railway lovers – and Togakushi Legend Murders, by Yasuo Uchida, both available in English on Amazon. I can promise you, you won’t be able to put them down! Hugh de Saram |