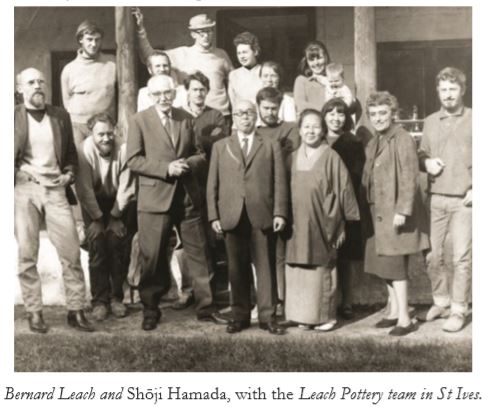

Tower and Town, May 2020 (view the full edition) (view the full edition)A Dragon In St IvesYou would have been witnessing the magic of working together of the legendary East-West soulmates: the younger Sh?ji Hamada (1894-1978) and the taller, Bernard Leach (1887-1979). They were to become giant figures within the pottery tradition. This is a brief account of the lives, friendship and works of the two who forged their legends within the crucible of the East-West exchange.

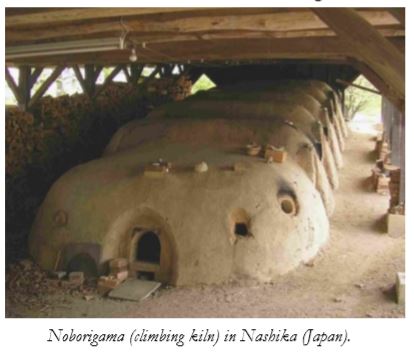

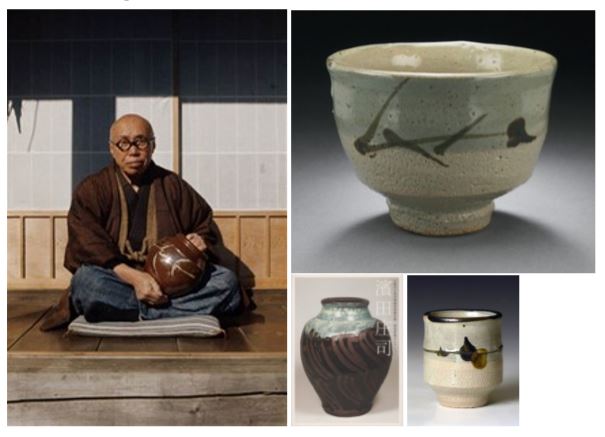

Where hearts are fused Leach travelled back to Japan in 1909 in order to practise etching and found himself associated with the Shirakaba Art Group which advocated opening up of Japan. He also found himself drawn to eastern philosophy and pottery, which he took up by 1911 after being inspired by the beautiful simplicity of the tea ceremony ware. He exhibited ceramics in Tokyo and studied under the renowned potter Urano Shigekichi, (Kenzan VI), before the end of the decade. Leach was then working in the tradition of Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743), who was a noted maker of raku ware; and in the process of doing so he earned the shared title of Kanzan VII, denoting the seventh generation of Kazan raku potters. (Raku ware is Japanese hand-moulded lead-glazed earthenware, originally invented in 16th-century Kȳoto by the potter Ch̄ojir̄o.) A younger Japanese ceramics technologist with aspirations to become a ceramic artist was much impressed with Leach’s Tokyo exhibition that he wrote to him in order to arrange a meeting. The young Japanese was Sh̄oji Hamada, who subsequently became his lifetime friend and collaborator. Hamada in fact accompanied Leach on his return to England in 1920 in order to help him set up Leach Pottery in St Ives, Cornwall, and build the climbing kiln (dragon) which formed the beginning of this article. Leach and Hamada inspired loyalty within the teams they formed over the years and drew inspirations from each other and their teams.

The Hamada effect

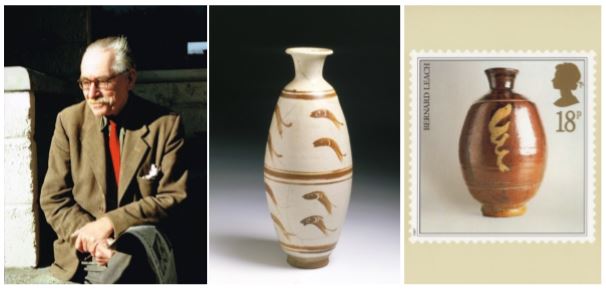

The Leach effect In fact many potters today work in the way he propounded in “The Potter’s Book”, which he wrote in Dartington in 1939 setting out his belief in the potter as a craftsman concerned in every aspect of the making, including the design and making of his own kilns. Leach’s work also fitted admirably into certain aspects of the Arts and Crafts Movement, especially the quietist and more anonymous-seeking ideals of those British potters that preceded him; although, ironically, he knew of William Morris through the Japanese philosopher Yanagi. Moreover, his lifelong fascination with the Far-East, and his recognition of the beauty and simplicity of the lifestyle and philosophy of its people, reflected in their crafts, made him a major contributor to the revival of pottery as a craft in the West. This was reflected in his aspiring to marry certain Far Eastern traditions with the mediaeval English style making him father of British Studio Pottery and a leader of the avant-garde movement of his day – a revolt by cultured people against the garishness of factory-made pottery.

Bernard Leach also gave St Ives its international reputation, and consolidated the status of the artist potter through international lecturing and publishing; including A Potter’s Book (1940) and the biographies Kenzan and His Tradition (1966) and Hamada, Potter (1975). You might be also interested to learn that an annotated edition of his 1978 “Beyond East and West: Memoirs, Portraits and Essays” is due to be published in August 2020 by Unicorn. Where hearts are buried And when you finally get overtaken by the galloping years and you begin telling stories of foolish times and loved ones, and of 1920 and its fire breathing dragon, a day might arrive when you would surprisingly find yourself actually in the pottery town of Mashiko in Japan. Some thick black smoke would be bellowing high in the sky and a person in the know would be animatingly pointing out that its source is the Mingie Pottery. So you would head there to find a not slumbering large dragon venting its heat and fire.

Some squeaking noise however soon would distract you to look into a room within a nearby outbuilding where two very old men would be sitting facing each other next to a window. They would have been sitting on an elevated wooden platform with their legs dangling within two rectangular openings containing foot-operated potter’s wheels. This would have set you wondering: it must have been few years……but there is something rather familiar! Suddenly the older and taller of the two, seated on your right at the larger platform opening, would have read your mind, nodded tenderly to his friend and turned smilingly to you and said: “And if you my old story teller wandered again atop the Stennack in St Ives, remember to tread carefully over where our hearts are buried”.

Raik Jarjis |