Tower and Town, February 2023 (view the full edition) (view the full edition)The Origins of the Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission'And when all was done, and the People of the Graves were laid at ease and in honour, it pleased the Padishah to cross the little water between Belait [England] and Frangistan [France], and look upon them. He give order for his going in this way. He said: "Let there be neither music nor elephants nor princes about my way, nor at my stirrup. For it is a pilgrimage. I go to salute the People of the Graves." Then he went over. And where he saw his dead laid in their multitudes, there he drew rein; there he saluted; there he laid flowers upon great stones after the custom of his people.' This extract from The Debt, a short story written by Rudyard Kipling in 1930, is based on Kipling's personal experience of the pilgrimage made by George V in 1922 to the battlefields and cemeteries of the Great War in Belgium and northern France. It captures perfectly the mood of a country four years after the end of that war paying homage to the hundreds of thousands of British and Imperial soldiers who had died between 1914 and 1918.

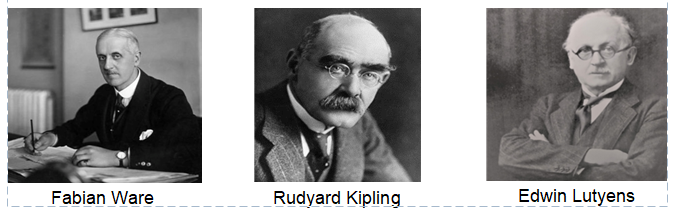

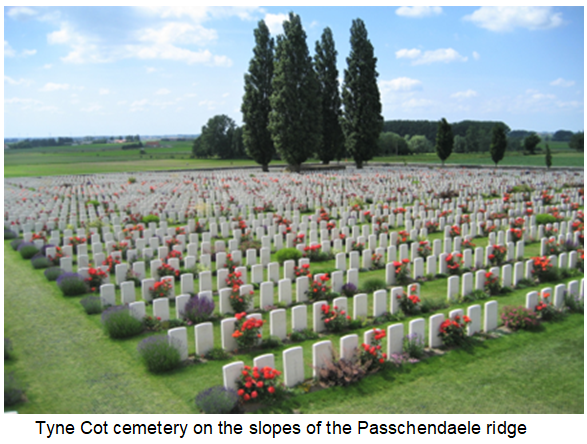

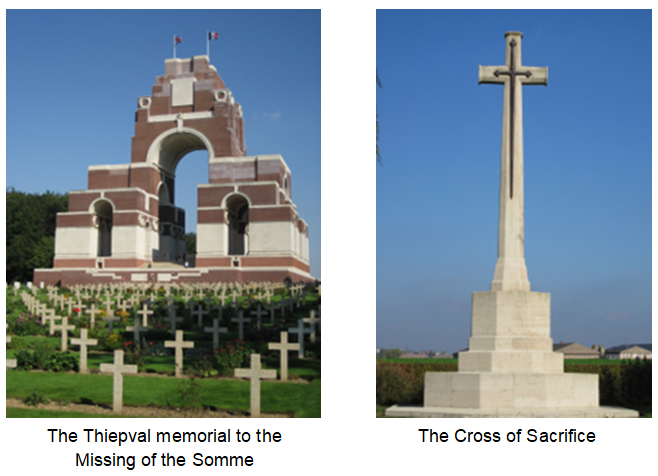

That it was possible to pay homage in this way was largely due to the remarkable inspiration and incredible effort of one man, Fabian Ware. Ware had had a varied career before the war but was clearly marked as a person of exceptional administrative ability. He was also an idealist, and that gave him the vision that was to become the driving force behind the creation in 1917 of the Imperial War Graves Commission. Ware was a volunteer ambulance driver at the start of the war, and quickly realised the need for some sort of organisation to trace the missing and record the dead. Using his powers of persuasion and ability to use contacts in high places, he managed to persuade the army to accept the responsibility for registering the graves of those who died in the war, and then most remarkably to get the French and Belgian governments to gift the land where the men of the British and Imperial forces were buried. Early on the great value of this registration to the morale of the troops and the British public became clear. General Haig commented on this work in 1915: "The mere fact that these officers visit day after day the cemeteries close behind the trenches, fully exposed to shell and rifle fire, accurately to record not only the names of the dead but also the exact place of burial, has a symbolic value to the men that it would be difficult to exaggerate." In May of 1917 Ware achieved the first part of his dream with the establishment of the Imperial War Graves Commission by Royal Charter. He then set about bringing on board some of the best people in the country to turn his dream into reality. Rudyard Kipling became literary advisor, capturing the spirit of commemoration in the simplest but most poignant of phrases - 'Known Unto God' on the headstones of unnamed graves; 'Their Name Liveth For Evermore' on the Stone of Remembrance. Edwin Lutyens, Herbert Baker, and Reginald Blomfield, three of Britain's most distinguished architects, were brought in to design the great memorials to the missing (Thiepval, Tyne Cot, and the Menin Gate) and to help with the planning of the cemeteries. Arthur Hill, top man at Kew Gardens, with advice from Gertrude Jekyll, was responsible for the planting of the cemeteries to create as near as possible 'the peacefulness of an English country garden'. Sir Frederick Kenyon, Director of the British Museum and President of the British Academy, wrote the report that became the bible of the IWGC and set the template for the great work of registration and burial that took place in the years immediately after the war. The result is a commemoration of the dead on a scale unmatched in human history. By 1927, ten years after the establishment of the Commission, more than 500 cemeteries on the Western Front had been completed, well over 400,000 headstones had been erected, sixty-three miles of hedges had been planted, 540 acres sown with grass. Across the world a thousand of Blomfield's Crosses of Sacrifice were up, 400 of Lutyens' Stones of Remembrance were in place, and the names of 150,00 missing servicemen had been inscribed on memorials. The Commission's Director of Works, Colonel Durham, told Ware on his return from a tour of half the world: "You have created a new Empire within and without the British Empire, an Empire of the Silent Dead."

Ware was determined that those who had paid the ultimate sacrifice in the Great War should be properly honoured, and so they were. There is no glorification of war in these cemeteries and memorials, indeed the opposite. As King George V said on his visit to Tyne Cot as part of his Pilgrimage in 1922: "In the course of my pilgrimage, I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon earth through the years to come, than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war."

David Du Croz |