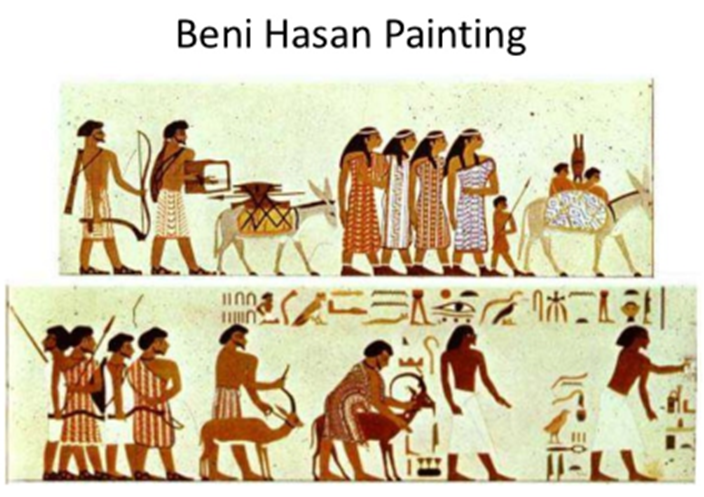

Tower and Town, May 2021 (view the full edition) (view the full edition)Biblical ArchaeologyOne of my first adventures on going up to Cambridge in 1965 to read Theology was being sent on a long bike ride down to the department of Oriental Languages for a class under the Regius Professor of Hebrew, David Winton Thomas. However, this was not a Hebrew class but an Introduction to Biblical Archaeology. It was indeed an adventure, introducing a whole new world, one of those great experiences where the mind is blown wide open and the horizon expanded beyond all expectation. To this day, I treasure my well-thumbed copy of Winton Thomas's Documents From Old Testament Times. What was so fascinating? Well, it put the narrow world of Biblical Israel into a much wider context. And we discovered that the Middle East is literally littered with that most romantic of objects, the clay tablet. We all know the story of Noah's Ark and the great flood that landed him eventually on Mt Ararat. What we discovered under Winton Thomas was that this story was most probably not originally an Israeli but a Mesopotamian story far older than its version in the Bible. Cuneiform clay tablets discovered in archaeological digs at Nineveh show it as part of a larger work, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and other, much earlier fragments of the same story have been discovered in similar digs elsewhere in Mesopotamia. There is even speculation - very speculative - that the story derives from the experience of populations fleeing the cataclysmic overflowing of the land bridge between Europe and Asia at the Bosphorus when sea levels rose at the end of the last ice-age and the freshwater lake that was the Black Sea was inundated with sea water from the Mediterranean. The realisation that the Bible is not the last word on many, many things and has to be rigorously fact-checked against other sources was quite disruptive to us as believers. Yet this was a kindly introduction, given that the Mesopotamian original behind our beloved Flood Story is delightful in its own right. For example, where the Bible story ends with a rainbow, the original has a mother-goddess raising her jewelled necklace into the sky. None of this felt like a contradiction of the Bible, merely an extension, an expansion. Moving on, however, we learned that the Biblical mention of camels in the Abrahamic era is an anachronism, a retro-fit by people writing much later, since the camel had yet to be domesticated in the time of Abraham. The clay tablets tell us of donkey caravaners but not camel caravaners. These semi-nomadic people, circulating around the edges of the Fertile Crescent and sometimes referred to in the tablets as Habiru or Apiru, often clashed with more settled people, whether over their herds trampling the crops in the fields or in more warlike encounters. We are lucky to have visual evidence of what these people may have looked like from a tomb painting in Beni Hasan, central Egypt. The colourful dress of the donkey caravaners, complete, it seems, with bellows for sustaining their fires (perhaps they traded in metal implements, the tinkers of their day) contrast sharply with the simple white dress of their Egyptian hosts. It is tempting to equate such scenes with Joseph's brothers seeking food in wealthy Egypt.  The Tel el Amarna letters (Egyptian clay tablets dating from the 14th century BC) is a collection of reports to the Pharaoh from governors in Canaan containing among other things complaints about attacks on their cities by Apiru who appear to be disrupting settled life in Canaan. Were these the loosely organised bands that eventually elbowed the Canaanites aside and coalesced into the people of Israel? It seems likely that not all, perhaps not even many, of those who ended up as the twelve tribes in Israel came from the group that left Egypt in Moses' train: many were there already but not as settled inhabitants. The Bible, archaeology suggests, gives us a selective, over-dramatised version. Another cause for reflection was the story of Jericho and Joshua's fabled tumbling of its walls. From 1952 to 1958 Dame Kathleen Kenyon led what has come to be regarded as an exemplary archaeological dig - at Jericho. The key thing we learned here was to do with dates. To cut a long story short, Kenyon found strong evidence that at the time when Joshua arrived before Jericho, its walls were probably already flat and had been so for some 200 years. So how come the discrepancy? The answer to this question came when I attended a British Museum lecture by a prominent archaeologist speaking on Biblical Archaeology. He confirmed that there was now wide agreement among scholars that the Jewish Bible, our Old Testament, had largely been written and assembled during and after the Babylonian exile, thus 6th century BC and later. Not surprisingly, the accuracy of their data probably diminished the further their subject matter was from the time of writing. Fair enough, perfectly human - but that's the point, isn't it: the Bible was actually written by humans; normal, fallible humans. Hugh de Saram |