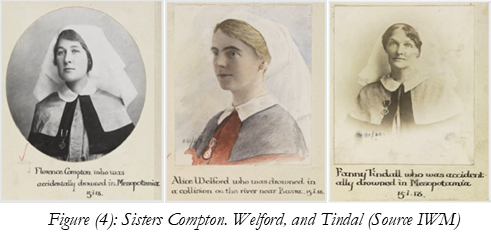

Tower and Town, May 2022 (view the full edition) (view the full edition)The Tragedy of the Mercy Angels in MesopotamiaIn November 1914, the war on the west Asian front escalated when the British forces marched toward Mesopotamia and landed in Basra. The British now aimed to control Mesopotamia to secure the route to Baghdad as a way station to the Russian army already stationed in northern Iran and to establish a line of defence against incursions by the Central Powers in central and south Asia. Additionally, the British wanted to secure the flow of oil from Persia, which had evolved as a cornerstone of their geopolitical and military strategy. Khuzestan's oilfields and the Abadan Oil Refinery were a mere sixty kilometres from Basra, and only the Shat al-Arab River separated Khuzestan from Ottoman Mesopotamia. During the summer months of 1917, as a consequence of the sinking of many hospital ships, five of the Maltese hospitals were transferred to Salonika. Nurses, among other medical staff, moved there in July 1917, experiencing even worse conditions with extremes of temperature and a high incidence of malaria. Hospital admissions alone during 1917 were numbered in tens of thousands. The Gallipoli Campaign of 1915-16, also known as the Battle of Gallipoli or the Dardanelles Campaign, was an unsuccessful attempt by the Allied Powers to control the sea route from Europe to Russia. Afterwards, the move of 12 nurses to Basra on 8 January 1918, after some six months in Salonika, must have come as a considerable relief as long as Basra was a flourishing strong base of the British army and many hundreds of miles away from the battle front up the Tigris. However, Basra proved to be far from a pleasant place. The young girls were attached to Number 3 British General Hospital established in the big Ashar's palace of Sheikh Khazaal, Emir of the Arab Emirate of Arabistan (now Khuzestan, Iran.)  Again, these girls were unfortunate and they were assigned to the extensions of the hospital comprising long prefabricated huts each with between 32 and 36 beds. Miss Marjery Swynnerton, a nurse also serving at the same hospital, wrote "Just less than two weeks after their arrival, a terrible tragedy occurred. A boat full of real VADs [Voluntary Aid Detachment] and their Matron (13 of them in all) had just arrived. They had been at Salonika where they had had a very horrible time after the Dardanelles fiasco. The ones I saw were jolly, pretty girls and everyone was out to invite them to parties and to make a great fuss of them and they had invitations en-bloc to all sorts of things. On the evening of the 15th of January 1918, they were all invited to a big dinner party down the river at a place called Mohammerah (c. 20 miles) and a motor launch was sent to fetch them. They never arrived. Their launch was cut in two by another boat in the dark and most of them were drowned. It was my unfortunate task to sit with the half-demented Matron who had been rescued, as the sodden piles of clothing were brought in for identification'. The investigations revealed: "A collision at Basra, shortly after sunset, between a Steam Tug and a Motor Launch containing a party of Nurses on duty." Four members of them died. The body of one (Miss Tindal) was recovered around the time of the accident and found that the cause of death being: "Suffocation by submersion and skull fracture" while the other three were reported missing, presumed drowned. The body of Florence Compton was found two weeks after the accident on 29th January, and buried the same afternoon in the Basra War Makina Cemetry, Ashar. The result of the Court of Enquiry was accidental death, due to: "An error of judgement on the part of the steersman of the launch." The victims were: Sister Florence D`Oyly Compton, Sister Alice Welford, Sister Fanny Tindall, and Sister Florence Mary Faithfull.  Preparing material for my book on medical service in Basra, I asked an old uncle of mine KO EL-Saleh three years before his death (1930-2020) about the tragedy. He told me what he had heard from his father who was an engineer with the Ottoman army and served in the Gallipoli war before he sought refuge and lived in Mohammerah after escaping from the army. The motor launch that the nurses took was crewed by two locals: the skipper sat on the back end and was the steersman and the other man sat at the front end with a paraffin lamp raised by hand to warn and light the way ahead. The early night of that Monday 15th of January 1918 must have been one of the darkest nights as it was the 22nd day in the lunar month. Ghanim Alsheikh, is a specialist in Neurosciences, Public Health and Medical Education. He was the founding dean of two medical schools in Iraq and Yemen (1988-2000) and served as WHO regional coordinator for the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. He is an associate at Imperial College London WHO Collaborating Centre and lives in Brighton. Ghanim Alsheikh |